Cartoon Halloween costumes were a lot different than today...

This is Fred and Wilma?

Monday, October 30, 2017

Friday, October 27, 2017

Rocky Memories: The Biographical Guide to Animation's First Lady

A while back, I posted the June Foray stories. They were widely successful. Today, I am officially writing a book on June. It is titled: Rocky Memories: The Biographical Guide to Animation's First Lady. I have helping me: Jerry Beck, Joe Bevilacqua, Mark Kausler, the Chuck Jones family, The Chuck Jones Gallery, David Nimitz, and many others. It is divided into three parts: a biography of her life, stories with the people who new her (like the ones on the blog), and interviews with her. I am writing this book and if you knew June, I'd love to speak to you to get more info on her life and your stories will be put in the book. To contact me, use the same address as the June Foray blogposts (comicspies@gmail.com).

Also, I'd love suggestions for things to put in the book. And if you know people who I should interview please feel free to tell me. people I can't find a way to contact: Keith Scott, Tom Sito, Leonard Maltin, Scott Shaw!, Bob Bergan, Jim Korkis, and Don Pitts.

Monday, October 23, 2017

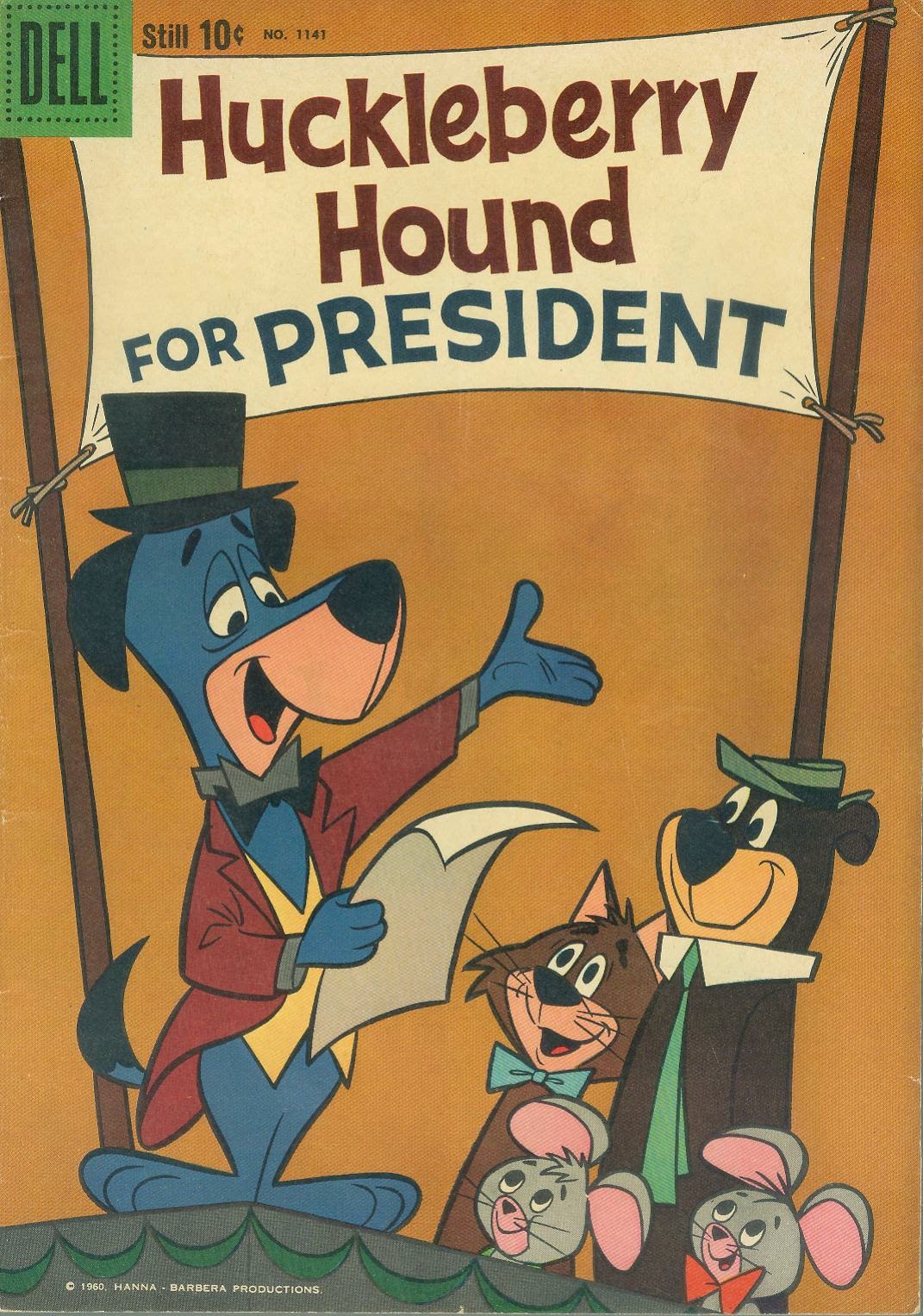

Huckleberry Hound For President Collectibles

As we all know from the Yowp and cartoon research, Yogi Bear and Magilla Gorilla both ran for president in print media. Before that, Huckleberry Hound For President. There was a bunch for collectibles and such on Huck running. Here are a few of the collectibles. To learn about the history of this, look at Yowp's post on this link Huck Hound for President--Yowp.

Record (A video of record)

Record (A video of record)

There was also a comic book about it. Here is the cover:

Here are Pinback Buttons

Sunday, October 22, 2017

Bullwinkle For President Pin

Bullwinkle for president pin. There was a rocky pin that was shown on a Bill Scott and June Foray interview but I can't find it.

Friday, October 20, 2017

Animated places—other destinations

There is a ton of animation destinations out there. Many of them we haven’t even heard of! Here a few more animated destinations. This is the last of this series.

1. The Rocky and Bullwinkle statue— As I mentioned last time, the Rocky and Bullwinkle Statue is a very iconic destination. This sat on sunset boulevard until 2015. Today it has been restored and is now at LA City Hall but will return to sunset soon (let’s hope).

1. The Rocky and Bullwinkle statue— As I mentioned last time, the Rocky and Bullwinkle Statue is a very iconic destination. This sat on sunset boulevard until 2015. Today it has been restored and is now at LA City Hall but will return to sunset soon (let’s hope).

2. The Warner Bros Mural--- A mural that contained all the Warner Bros owned characters and was outside the WB studios.

Friday, October 13, 2017

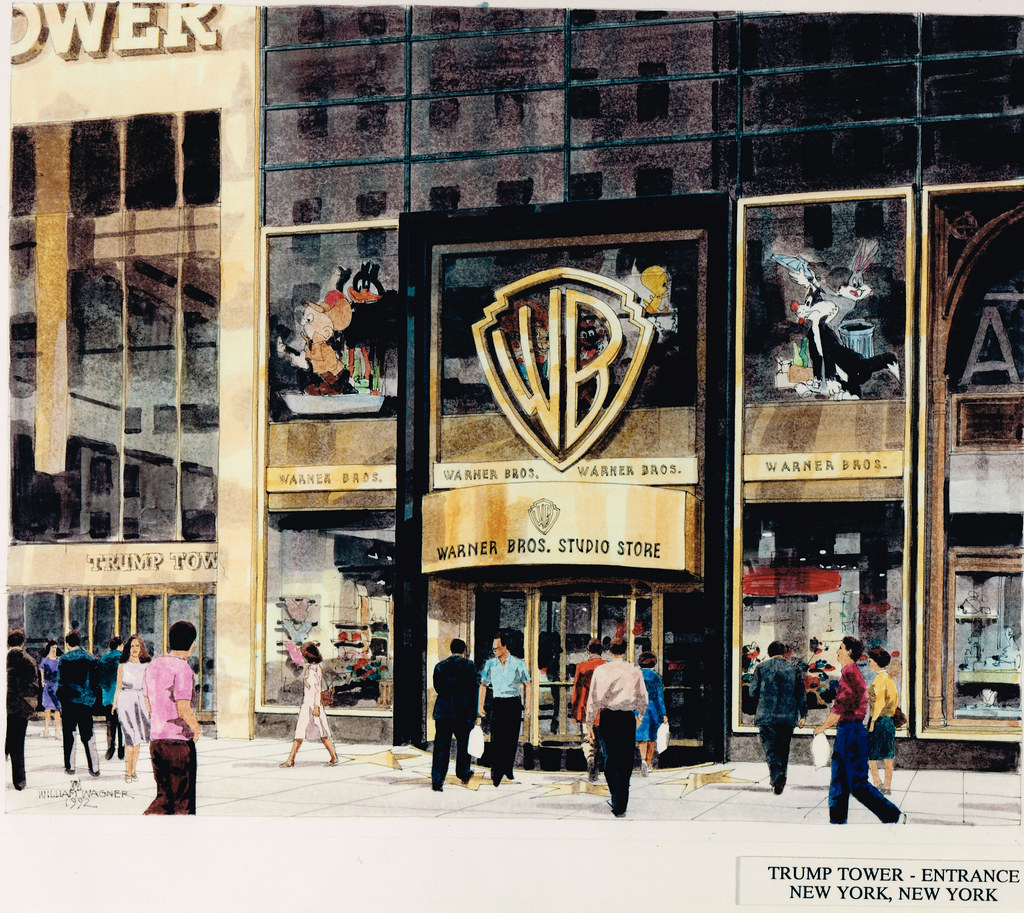

Animated Places Part 2--- Stores

There has been many stores about our favorite animated characters but I am going to talk about 2. The Warner Bros Store and the The Dudley Do-Right Emporium.

1. The Warner Bros Store were around the country. The store contained a ton of Looney Tunes merchandise and would later contain HB stuff after Warner Bros bought Hanna-Barbera. Warner Brothers stores were replaced by Disney Stores which were replaced by Nickelodeon Stores. It just worsens. Today, there is no Nickelodeon Store.

2. The Dudley Do-Right Emporium was a store that sold Jay Ward items. It was run and owned by Jay Ward. In fact, you could see Jay Ward there. It closed in 2005. It was located at 8200 Sunset Boulevard which was close to the former Jay Ward Studios. It opened in 1971 and was right behind the Bullwinkle statue. That statue is going to return to that spot soon. Next post will be about statues such as that.

1. The Warner Bros Store were around the country. The store contained a ton of Looney Tunes merchandise and would later contain HB stuff after Warner Bros bought Hanna-Barbera. Warner Brothers stores were replaced by Disney Stores which were replaced by Nickelodeon Stores. It just worsens. Today, there is no Nickelodeon Store.

2. The Dudley Do-Right Emporium was a store that sold Jay Ward items. It was run and owned by Jay Ward. In fact, you could see Jay Ward there. It closed in 2005. It was located at 8200 Sunset Boulevard which was close to the former Jay Ward Studios. It opened in 1971 and was right behind the Bullwinkle statue. That statue is going to return to that spot soon. Next post will be about statues such as that.

Thursday, October 12, 2017

Animated Places part 1-- Theme Parks

A while ago I talked about the Popeye town in Illinois. Here is a sequel to that: animated places. Part 1 is theme parks and tourist spots. This is not about Disney or Universal Studios. This is about forgotten or rarely mentioned or needed to be mentioned parks that are both closed and are not. Note: Six Flags and Jellystone Park are not included.

1. Bedrock City----This was the first park by Hanna-Barbera. I believer they're all closed but the first one that opened was in Custer City South Dakota near the Black Hills. It only closed in 2015 but it opened during the Flintstones 6th season in 1966. There was then one in Arkansas and that remains open. In these parks you got (or get depending on which one) to watch cartoons at the Bedrock Theater, eat Bronto Ribs and Bronto Burgers, see Fred and Barney's house as well as the slates and Gruesomes, play golf (mini), go bowling, and all sorts of other fun things.

1. Bedrock City----This was the first park by Hanna-Barbera. I believer they're all closed but the first one that opened was in Custer City South Dakota near the Black Hills. It only closed in 2015 but it opened during the Flintstones 6th season in 1966. There was then one in Arkansas and that remains open. In these parks you got (or get depending on which one) to watch cartoons at the Bedrock Theater, eat Bronto Ribs and Bronto Burgers, see Fred and Barney's house as well as the slates and Gruesomes, play golf (mini), go bowling, and all sorts of other fun things.

Youtube video of home movies of a family Bedrock City in 1968

2. Hanna Barbera Theme Parks--- Hanna Barbera had many theme parks including King's Island and Hanna-Barbera Land. There is none now but they were very popular at one time.

Another video but of HB Land

3.

Monday, October 9, 2017

Bugs Bunny and Petunia Pig

Honey Bunny was Bugs’ first official girl. Before her, Bugs was constantantly with Petunia (often on covers)! It’s kind of weird. Why? Why would Bugs want Petunia? Here are covers—

Wednesday, October 4, 2017

Chuck Jones: Our Greatest Silent Actor

Here is an article from the Atlantic. It's about Chuck Jones and it was published in 1984 and written by Lloyd Rose.

CHUCK JONES IS one of the great silent clowns of the screen, though he has only once appeared in front of the camera. He did a walk-on under his own name (Mr. Jones) in Gremlins, a movie that is on one level a tribute to the art that Jones brought to its peak--the anarchic Warner Brothers style of animation. Jones worked at Warner Brothers as a director for twenty-five years, during which he developed Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck to their full comic richness and, along with his scriptwriter/gagman Michael Maltese, created the Coyote and his prey and nemesis the Road Runner.

It's true that Jones's cartoons are violent, but his characters never bleed, never die, and are never permanently injured; they have an India-rubber resilience, the immortality of handballs. They also have wit, style, and humor. And it's getting harder and harder to see them. The newly packaged The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Show, seen on Saturday morning, is (unlike its predecessor of the same name, which featured Jones's cartoons) filled mostly with the second-rate cartoons made at Warners by inferior directors in the early sixties, during Jones's final years there. (Now seventy-two, Jones has for the past twenty years produced his own television specials--the most famous of which is How the Grinch Stole Christmas.) Occasionally one of his cartoons flashes across the Saturday-morning TV screen. In such shabby surroundings the vitality and beauty of his work stands out even more boldly than usual.

The key to Jones's brilliance is that he is an actor--but he acts with bodies he draws rather than with his own. As a boy, he lived a couple of blocks from Chaplin's studios, and he used to go down after school and watch Chaplin film. From this he learned not only technique but, watching Chaplin do a take again and again, patience and fanatical attention to detail. Though he never became an actor, he was to continue and preserve the art of silent-screen comedy, through a series of more than 200 cartoons, up till the early sixties.

Bugs, Daffy, the Coyote, and the romantic French skunk Pep6 le Pew are not characters that Jones puts into cartoons as a novelist might put them into a story--they' re characters he plays. They all share certain characteristics: high energy, expressive eyes, exquisite comic timing, and the ability to surprise us. We recognize these characteristics in all of them as we recognize the physical presence of an actor in various roles. To give them individuality, Jones brings to each an element of his own personality. The Coyote represents his inability to deal with certain things in the physical world, particularly tools. Pepe le Pew is his dream vision of himself as irresistible to women. Bugs is the inoffensive guy who, when roused, is as unbeatable as Groucho Marx. Daffy, whose motto is "I may be mean but at least I'm alive," is the complete survivalist. Unlike a flesh-and-blood actor, Jones has the privilege of playing two or more characters simultaneously. Some of his funniest cartoons result from matching the unflappable and ironic Bugs with the desperate and treacherous Daffy. Daffy plots against Bugs; Bugs eludes him with lazy ease. Daffy, through greed, falls into trouble; Bugs, sighing, rescues him.

BUGS WAS DESIGNED by Charles Thorson at the request of the animator Ben "Bugs" Hardaway (and labeled "Bugs' bunny"), and his personality as a Brooklyn wiseacre cockily demanding "What's up, Doc?" was the creation of Tex Avery (who also invented the wild, nonrealistic Warner Brothers animation style). Jones, though, directed more than half of the Bugs cartoons made, and has said that Bugs "was something more personal and special to me ... than any other character I directed."

Jones's Bugs is easily distinguishable from that of any other director. His movements give the sense that he has real mass and inertia, that he weighs something, and Jones has frankly borrowed for him gestures from the great silent comedians (Keaton's eye movements, Chaplin's one-legged hopping turn). His Bugs also has sophistication--he is less the loudmouthed wise guy, more the gentleman anarchist. (In spite of the mad pace of his cartoons, Jones is never frenzied--his characters all possess a certain amount of dignity. This is why his work at MGM, where he went after Warner Brothers shut down its animation studio, isn't successful. The crudely violent format of the Tom and Jerry cartoons he was given to direct is at odds with his comic sense and style. His Tom and Jerry seem not to belong to the world established by the series; they're too sweet-natured.)

Jones always liked to start with Bugs in a setting natural to a rabbit (unlike, say, the Friz Frelengcartoon in which he is introduced tap-dancing down the street singing "She's the daughter of Rosie O'Grady"). Having limited himself with this rule, Jones developed a comic way of both sticking to and circumventing it: when he wanted Bugs in an exotic locale (Scotland, maybe, or the Himalayas), he just had him pop suddenly out of the ground, expecting to have burrowed to somewhere else. Bugs's grace under pressure is literal--he floats, dashes, and, in one lyrical moment in "Bully for Bugs," dances away from his persecutors. Bugs can rise to any occasion. In "What's Opera, Doc?"--arguably Jones's finest cartoon--he dons a blonde wig and a brass brassiere to sing a Wagnerian duet with Elmer Fudd (who has previously regaled us with "Kill the Wabbit!" to the melody of "The Ride of the Valkyries"). Bugs dances in this one too, as does Elmer. They do a little ballet together, while an ample white horse, supplying the fleshy operatic presence that the more slender protagonists lack, minces like a prima donna in the background.

Bugs does not need sound to realize much of the comedy of this--it's there in his expressions and gestures. But he does speak, of course, and the parody of "What's Opera, Doc?" would be lost without the music. Jones and Maltese actually wrote pretty funny dialogue (Pep6 le Pew's amorous murmurings-"Ah, la belle femme skunk fatale!"-are particularly good), but the cartoons, despite the bravura vocal performance of Mel Blanc as most of the characters, don't depend on it. Jones used to run his cartoons without the soundtrack just to be sure everything was clear even without the words. But he didn't take the final step into silent comedy until the Road Runner cartoons, in which the only spoken sound is "Beep! Beep!"

Jones and Maltese created the Road Runner in 1949, and Jones went on to make twenty-four Road Runner cartoons. They're minimalist in an amusingly practical way--Jones provided for the setting only what the story needed. This is basically a desert, with a highway for the Road Runner to run down. There are also, as needed, train tracks for the Coyote to get run over on, train tunnels for the Coyote to get run over in, and cliffs for the Coyote to fall off. And there is the occasional mailbox, so that the Coyote may write to the Acme Company and order devices with which to trap the Road Runner. (It hardly seems necessary to add that these devices not only always fail to catch the bird but invariably backfire in the Coyote's face.)

After the first few cartoons Jones didn't even bother to have the Coyote pursue the Road Runner from hunger. He just chases him, without reason or possibility of success. The bleak undertone of his predicament combined with the stripped-down environment gives the cartoons a modernist feel--sort of banana-peel Beckett. But essentially they're gag pictures: their comedy is mainly in the setup, the buildup, and the payoff of the physical joke, as well as the overall shape of the action. The Coyote runs a taut wire from the top of a cliff down to the road along which the Road Runner will pass. He dons a helmet with a tiny wheel on top of it. He headstands onto the wire. He quivers from side to side, searching desperately for balance, just missing it; we expect he will fall any second. He finds his balance. He settles into upside-down equilibrium. He is perfectly poised. The wire snaps. At moments like this, Jones stands with Keaton and Chaplin.

Jones achieved his comedy through the design and manipulation of drawings that move past the viewer at twenty-four frames a second. His timing was a matter of knowing how many twenty-fourths of a second to hold a pause or track a fall. As a director Jones didn't draw anywhere near the 8,000-plus pictures necessary for a six-minute cartoon. He did two or three hundred drawings, the beginnings, ends, and high points that shaped and defined each physical action. The rest of the work was done by Jones's animators (for most of his career they were Lloyd Vaughan, Ben Washam, Ken Harris, Phil Monroe, Dick Thompson, and Abe Levitow), who filled in and gave their own touches to the character's movements. These animators in turn had in-betweeners to do those last cells that account for the minuscule movements an arm or tail might make in three or four frames.

Disney, whose sentimental and hyperrealistic style the Warner Brothers cartoonists rejected, was nonetheless the father of their art: expression of character through movement. Jones (who worked for Disney very briefly, on Sleeping Beauty) considers The Three Little Pigs to be the breakthrough film. The pigs all look alike but are distinguishable by their postures and expressions. Jones calls this "character animation," and has said it is "unique to America, like jazz," laying claim to it as one of our few native art forms. The Warners cartoons, like those of Disney, were made to be shown in movie theaters to adult audiences. Those audiences wept at Snow White in 1938, and an adult today watching a Jones cartoon from the fifties may laugh till tears are in his eyes.

Lloyd Rose writes on film and theater for The Atlantic.

Rose, Lloyd

Credits: The Atlantic, Gale Databases

Tuesday, October 3, 2017

Bullwinkle and The Simpsons

By Rob Holly

"The Simpsons' Father Speaks"

© Cards Illustrated, Issue 9, September 1994

© Cards Illustrated, Issue 9, September 1994

Which ones in particular did you grow up with?

Groening: All the Warner Brothers cartoons: Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Road Runner. I was also a big fan of Droopy by Tex Avery and the Fleisher Brothers' Popeye and Betty Boopcartoons. Of course, Disney features, shorts, and I think the biggest influence as far as my work in animation was Rocky and Bullwinkle.

Rocky and Bullwinkle was a cartoon that was very cheap looking, but it worked anyway. And I figured that what made this cartoon work was great writing, great voices and great music, and that the animation didn't matter as much.

By John W. Kim

"Keep 'em Laughing"

Groening's inspiration to create a show came from such classic television animators as Jay Ward. "When I saw Rocky and Bullwinkle I realized that you didn't necessarily have to be a great cartoonist or artist to make a great cartoon," says Groening. "All you needed was great writing."

Also before the end of this post, here is some trivia you may not have known

Homer, Abraham, Bart and Chester Lampwick's middle intial `J' is a tribute to Rocky & Bullwinkle (Rocket J. Squirrel & Bullwinkle J. Moose), whose initials were in honor of their creator, Jay Ward.

Thanks to The Simpsons Archive

Monday, October 2, 2017

Matt Groening and Mel Blanc

Matt Groening

By Erik H. Bergman

"Prime time is heaven for 'Life in Hell' Artist"

© TV Host, December 16, 1989

© TV Host, December 16, 1989

Credit: The Simpsons Archive

Groening the student put down his pen and paid attention for at least one day. He attended the same school - Portland's Lincoln High - as Mel Blanc, voice of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Barney Rubble and others. He recalls how Blanc spoke in 1969 at the school's centennial. Everything from hair length to Vietnam war protests to racism made for a divided school. Blanc's assembly "was one of the most memorable, happy events in a raucous time. Virtually everybody in the school, from the hippies to the hoods to the teachers to the scowling administrators, was laughing. It was the one time the school was really united."

Sunday, October 1, 2017

The Mysterious Voyage of Homer: What's Opera Doc? of The Simpsons

The Mysterious Voyage of Homer: What's Opera Doc? of The Simpsons

It took a while to make this episode. Here is what Robert Vasquez had to say.

Robert Vasquez: Well! Now we know why it took so long for this episode

to appear. I imagine Gracie Films treated this episode as an

extra-special event, like Chuck Jones and "What's Opera, Doc?" The

backgrounds in the hallucination were breathtaking, and Johnny Cash

was better than perfect as the coyote spirit-guide. I only wish I'd

taken a look at my dad's Carlos Castaneda books so I'd have some more

insight into the parody.

Special thanks to The Simpsons Archive for permission to use this

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)